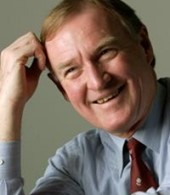

Margaret's son, Lt Mark Evison, was shot in Helmand, Afghanistan: he died a few days later. Margaret subsequently wrote a powerful book 'Death of a Soldier' which is to be dramatized on BBC Radio 4 to mark the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Mark wrote a diary whilst in Helmand, which was published in the Daily Telegraph on 14 July 2009. 'The circumstances of Lieutenant Evison's death became a prominent element in the debate and controversy in Britain at the time over how the Afghanistan campaign was being fought and particularly how it was being resourced - of which the political sandstorm over the alleged lack of helicopters was just one part. The young officer kept a detailed journal, key parts of which attracted attention when they first appeared in public.' (Nick Childs, BBC War Correspondent, RUSI Journal 2013).

At the time Margaret was made aware of the need for better equipment for frontline soldiers, communications and helicopters, and was able to help make the public become better informed about the war, with so many deaths following in 2009/10 and subsequently. She has been interviewed many times, including in 'Woman's Hour', the Today programme (twice), BBC Breakfast, Newsnight, Channel 4 News, and in many newspapers and magazines. She has written for Prospect Magazine, the Guardian, and in 2014 the RUSI Journal. She spoke at the Defence Academy in 2013.

Immediately after Mark's death, Margaret and his friends set up the Mark Evison Foundation 'to promote the personal, mental and physical development of young people'. The Foundation gives awards to young people 16-30 years for non-academic personal challenges that applicants propose, plan and carry out themselves. Its strapline is 'bring out the best in you'. It aims to give awards to young people who lack opportunity and by the end of 2013 there were 57 beneficiaries. www.markevisonfoundation.org

In 2013 Margaret was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Oxford Brookes University for this work.

In 2012 Margaret's award-winning book 'Death of a Soldier' was published - it includes Mark's journal. She writes about Mark's death, how it impacted on those at home and the soldiers, about the Coroner's inquest and about visiting Afghanistan. It has been very well reviewed and published internationally as well as translated into Marathi.

Professor R Jones in the Br.J General Practice, says 'What emerges is a truly gripping- and exceptionally well-written - story of incredible bravery, tragedy, bungling, dishonesty, and magnanimity.'

The book was selected as Military Book of the Year by the Times Defence Editor in 2013. It is to be dramatised by BBC Radio 4 this year to mark the withdrawal from Helmand, and Margaret has presented it at major literary festivals in the UK and Australia, including the Hay Festival.

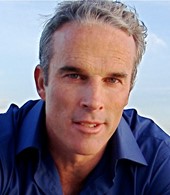

A Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Margaret led the cancer support team at Guys and St Thomas' Hospital Trust for 14 years. She now has a private practice. She is a Trustee of Dimbleby Cancer Care.

Margaret's professionalism, intelligence and thoughtfulness make her a fascinating speaker working to make something positive come from the tragedy of Mark's death.

Rusi Journal December 2013

Death of a Soldier:

A Mother's Story

Margaret Evison

Biteback, 2012

Lieutenant Mark Evison of the Welsh Guards was shot and gravely wounded on 9 May 2009 while leading a patrol in the Nad-e Ali district of Helmand Province in Afghanistan. He was flown back to Britain, but died from his injuries three days later in Selly Oak Hospital in Birmingham. He was twenty-six and had been in Afghanistan for less than a month, on his first tour.

Death of a Soldier, written by Mark's mother Margaret, is a moving account of his life and death, and the aftermath of his death, from her perspective. In a sense, it is a tale as old as history, and there have been many such deaths - 'old war cemeteries speak of these'. But the fact of this book, the sequence of events it relates, and the fact that we know of this particular young man's death are testimony to there now being something different about how we view such loss.

Margaret Evison writes affectingly and elegantly about the swirl of emotions and memories she felt as she saw her son go off to war and first received the news that he had been shot, as well as the limbo of uncertainty and anxiety that followed, and the human drama in Selly Oak Hospital as the family had to let go and Mark's life-support machines were switched off. But this book is also about how the author's mix of sadness and grief turned to anger and frustration as she felt the authorities refused to answer her questions about the circumstances of her son's death - including why it took as long as it did for a rescue helicopter to arrive and whether his platoon's radios were working properly - fuelled by her dissatisfaction at the way in which the inquest into her son's death was handled.

It also explains why the circumstances of Lieutenant Evison's death became a prominent element in the debate and controversy in Britain at the time over how the Afghanistan campaign was being fought and particularly how it was being resourced - of which the political sandstorm over the alleged lack of helicopters was just one part. The young officer kept a detailed journal, key parts of which attracted attention when they first appeared in public. And it is quoted extensively here.

The key passage, written on 21 April 2009 less than three weeks before he was shot, seemed to offer evidence from the front line, as it were, of what many critics felt was going wrong: 'As it stands I have a lack of radios, water, food and medical equipment. This with manpower is what these missions lack. It is disgraceful to send a platoon into a very dangerous area with two weeks' food and water and one team medics pack'.

Of course, families of the past may also have questioned, in many instances, whether their loved ones had died needlessly, because of poor planning or a lack of resources. What is different now is the fact that the whole political, social and legal context in which conflict is conducted has transformed dramatically. And the degree of public tolerance of casualties - whether friendly, enemy or innocent - is dramatically less in these distant 'wars of choice' like Afghanistan.

That has been reflected in the controversy over Afghanistan, in whatever the 'Wootton Bassett effect' represents, and the legal proceedings over the army's duty of care that relatives of casualties from Iraq have been pursuing. This will surely have an impact on how and whether military interventions take place in the future.

It is a paradox that fewer families may now be affected directly by losses like that of the Evisons than in past conflicts. Yet the grit and danger of the fighting has been brought home to many more people in their own living rooms through the power of helmet cameras and the other visceral footage that has been aired more than ever before.

One of the most compelling parts of the book is the accounts of Lieutenant Evison's comrades as they desperately tried to carry him to relative safety and call for help after he had been shot, as he almost literally bled to death before their eyes. What adds to the impact of these accounts is that one can visualise both the incident itself and others as one reads. Indeed, perhaps one of the greatest values of this well-written book is that Margaret Evison is able to make the connection between what we have all seen on our television screens and what it means for those who suffer the loss in a very personal way.

As Mark's mother writes, 'I understand more completely now that when there is love there will also be pain and suffering'. Her fond, proud recollections of her son are the natural ones of a mother who saw Mark begin life as a sickly child, go through 'years of erratic academic achievement', but blossom into a handsome, charismatic young man who thrilled in adventure and found his calling with the British Army. One of the most poignant passages in the book is Mark's last army report, which speaks of 'an exceptionally impressive officer', with characteristics which 'bode well for a notable military future'

Margaret Evison writes affectingly and elegantly

Nick Childs also says 'The fact that Margaret Evison could write this very accessible account, and that she was also able to find a way to visit Afghanistan to see for herself the country in which her son died, also marks her out as a rare individual. The questions and doubts she raises about how the campaign has been conducted and what it has all been for may be fairly conventional. But what is contained in her account may gain ever-greater relevance as the close of the campaign draws nearer, and the jury continues to debate what exactly has been achieved and at what cost.'

The Spectator reviewed the book in January 2013 "She writes 'The muddle over Mark's death seemed to reflect a more fundamental Army and political muddle over Afghanistan, as well as a muddle about itself.' Of all the epitaphs that will be written about our presence in Afghanistan, this may turn out to be the most damning of all."

A dynamic and versatile speaker, Josh is able to draw upon his experience and expertise to give inf…